An Army of Virus Tracers Takes Shape in Massachusetts

Asian countries have invested heavily in digital contact tracing, which uses technology to warn people when they have been exposed to the coronavirus. Massachusetts is using an old-fashioned means: people.

By Ellen Barry

Published April 16, 2020 Updated April 17, 2020

BOSTON — Alexandra Cross, a newly minted state public health worker, dialed a stranger’s telephone number on Monday, her heart racing.

It was Ms. Cross’s first day as part of Massachusetts’s fleet of contact tracers, responsible for tracking down people who have been exposed to the coronavirus, as soon as possible, and warning them. On her screen was the name of a woman from Lowell.

“One person who has recently been diagnosed has been in contact with you,” the script told her to say. “Do you have a few minutes to discuss what that exposure might mean for you?” Forty-five minutes later, Ms. Cross hung up the phone. They had giggled and commiserated. Her file was crammed with information.

She was taking her first steps up a Mount Everest of cases.

Massachusetts is the first state to invest in an ambitious contact-tracing program, budgeting $44 million to hire 1,000 people like Ms. Cross. The program represents a bet on the part of Gov. Charlie Baker that the state will be able to identify pockets of infection as they emerge, and prevent infected people from spreading the virus further.

This could help Massachusetts in the coming weeks and months, as it seeks to relax strict social-distancing measures and reopen its economy.

Contact tracing has helped Asian countries like South Korea and Singapore contain the spread of the virus, but their systems rely on digital surveillance, using patients’ digital footprints to alert potential contacts, an intrusion that many Americans would not accept.

Massachusetts is building its response around an old-school, labor-intensive method: people. Lots of them.

“It’s not cheap,” Governor Baker, a Republican, said. “But the way I look at it, the single biggest challenge we’re going to have is giving people confidence and comfort that we know where the virus is.”

The state is currently experiencing a surge of cases that is expected to last for the next week, after which it may start to consider easing social-distancing rules. Robust contact tracing, combined with ramped-up testing, could smooth that process, the governor said.

“It’s hard to see how we create a sense of safety if we don’t have a program like this in place,” he said.

The idea of training a corps of contact tracers is emerging in many places at the same time, as leaders think ahead to the point when social-distancing constraints will be lifted.

President Trump was expected to announce that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would hire hundreds of people to perform contact tracing as part of his push to allow the country to go back to work and school, a top government official said this week. San Francisco is assembling and training 150 volunteers to augment the contact-tracing efforts of its own public health department. Ireland is deploying 1,000 furloughed government workers to do contact tracing.

This means restoring capacity that has been pared away for decades by cuts to public health budgets, said Allyson Pollock, the director of the Institute of Health and Society at Newcastle University in the northeast of England.

“All our fancy scientists think it’s boring, because it’s people, you need people on the ground,” she said. “It’s the hard bread and butter of communicable disease control, and we’ve decimated our services.”

The Massachusetts program is staged by the nonprofit Partners in Health, whose doctors have led responses to infectious disease — Ebola, Zika, drug-resistant tuberculosis, cholera and typhoid fever, among others — in the world’s poorest countries.

It is built around one-on-one telephone interviews of newly diagnosed patients and their contacts, so that subjects must answer the phone when it rings. Paul Farmer, a physician-anthropologist and one of the group’s founders, said there was no substitute for the bond of trust formed by a human contact tracer.

“Somebody needs to say to people who are worried and not feeling well, ‘We got you,’” he said. “‘If this is Covid-19, we got you. And we’ll look out for your contacts, your spouse and your children.’ And I think that’s another thing you can do remotely or virtually, is reassure people that there is no reason to believe everything is lost.”

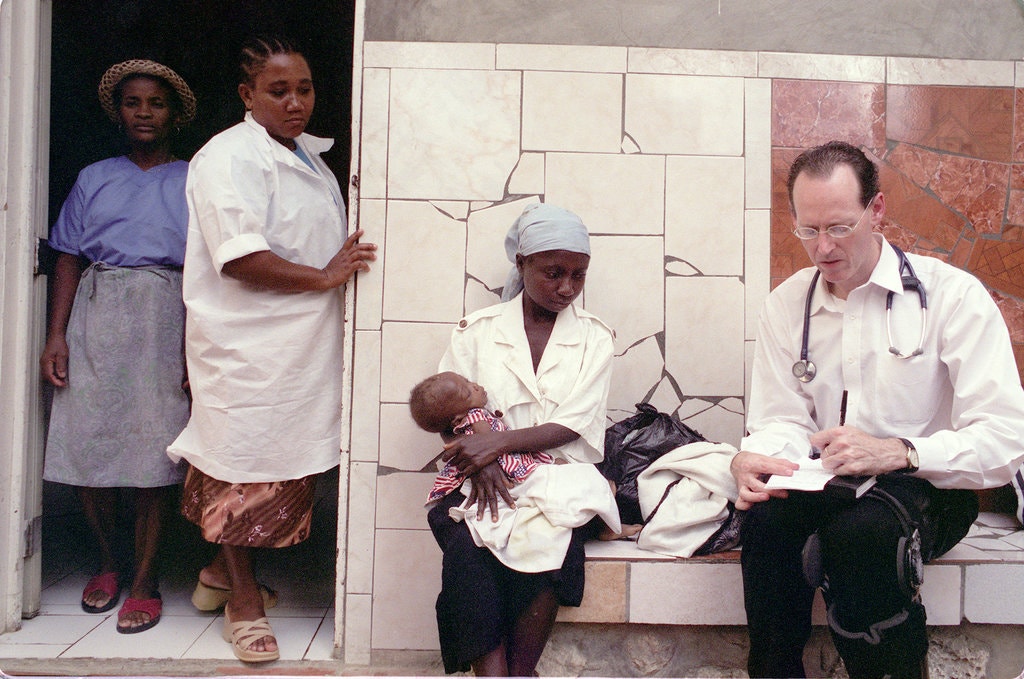

Dr. Paul Farmer, in Cange, Haiti, writing a prescription for a mother whose child was suffering from starvation. Credit…Ángel Franco/The New York Times

Dr. Farmer, 60, whose work on tuberculosis gave him a kind of rock-star status in the public health world, tried to calm the nerves of around 80 new recruits last week, describing his own experience investigating a tuberculosis outbreak as a medical student.

His eyeglass frames had broken, something he cheerfully blamed on the pandemic, and he had to balance them on the bridge of his nose as he spoke.

“Once you get in someone’s space — this is going to be different, to the extent that it is virtual — but sitting with folks in their homes, the subtext of these tracings was, ‘Hey, we want to help you and your family,’” he said.

The downside of human contact tracing is that it is expensive, can overlook contacts a subject may not recall, and, some argue, is too slow for a fast-moving virus.

“Using automation to do it, cellphones and triangulations of data, that is the easiest and fastest way, and probably the most effective way to do this,” said Ranu S. Dhillon, a physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who advised the government of Guinea on the Ebola outbreak.

“If you’re taking one or two days to manually figure out where someone went, you’re adding more time where people can transmit it to others,” he said.

But human outreach is a standard public health practice, first used in many countries to seek out sexual partners of men and women known to be carriers of sexually transmitted diseases.

It was gritty, solitary work. A contact tracer who worked in New Zealand in the 1970s described spending her evenings in bars and boardinghouses, tracking down subjects based on sketchy descriptions, like, “she goes to the hotel at Friday nights and she drinks Southern Comforts,” and “Kathleen — with a generous superstructure.”

The work required such abnormal hours and such secrecy, the contract tracer told the historian Antje Kampf that it was difficult to have a social life or marriage. “I sometimes wonder if I was chosen for the job because I was a loner, or if it was the other way around,” she said.

In recent years, jolted by SARS and then by MERS, Asian countries have poured resources into contact tracing, combining sophisticated digital tools with large networks of public health outreach workers.

Jim Yong Kim, a co-founder of Partners in Health, who recently stepped down as president of the World Bank, said he was struck by the contrast between American and South Korean leaders, who, because of robust contact tracing, felt able to go on the offensive against the virus.

“We’re sitting back, hunkering down, waiting to see what the virus is going to do to us,” he said. The language of South Korean colleagues, he said, “was completely different from the language I was hearing in the U.S. They were talking about the virus as if it were a person. Telling me how tricky it was. It was the experience of chasing it down.”

In a late-night phone call at the end of March, Dr. Kim pitched his idea to Governor Baker, pointing to data from Wuhan, China, that showed that social distancing alone could not bring the virus’s spread rate low enough to lift the current restrictions.

“When people say you can’t do that, it’s too labor-intensive, it makes no sense to me,” he said. “Ask all the people sheltering in place, the 70 percent of people who have lost income — I would ask those people, how much is it worth to us to really get on top of it? $100 billion? $500 billion?”

Governor Baker, who listened to the pitch in his car that night, said he appreciated that Dr. Kim could point to concrete experiences of battling outbreaks in African countries and in Haiti.

“I have people reaching out to me all day with theoretical things that we could do, God love ’em,” he said. He said he had also heard from “everyone who had a phone-pinging program,” and that digital tracing may be integrated into the state’s program later, but that human outreach was critical to reaching people without an easy way to isolate themselves.

“You’ve got to be able to connect to people in some way that’s meaningful that’s beyond a ping on the phone,” he said.

Already, Massachusetts’ local departments of health had been carrying out contact tracing, assisted by 1,700 volunteers from the state’s academic public health community.

The 1,000 new jobs, announced at a news conference on April 3, set off a deluge of applications, now numbering around 15,000. Ms. Cross, 27, who is training to be a nutritionist, said she was so emotional about taking part that she wept during her recorded interview.

recorded interview.

Dr. Farmer leading a training session, by video, for new contact tracers on April 9.

“I feel like I have all this energy that I want to funnel into prevention,” she said.

Harvey Schwartz, 72, a retired civil rights lawyer from Ipswich, said he sent in his application within 15 minutes of Governor Baker’s announcement, offering to work without pay.

“I’ve been spending two and a half hours every morning reading the news, and getting more and more depressed,” he said. “This is the antidote to that.”

“Cohort One” of the state’s program — a group of around 80 hires, among them graduate students, Peace Corps volunteers, medical assistants and retired nurses — logged on for the first time last Thursday, to learn the nuts and bolts of the system.

Each time a citizen tests positive, the results will be immediately shared with a case investigator through a secure database. Within two hours, the case investigator will aim to reach the patient by phone and compile a list of every person he or she had been in close contact with in the 48 hours before the onset of symptoms.

The names of the contacts — the expectation is 10 people per new case — will then be passed to contact tracers, who will attempt to reach each one by telephone within 48 hours, calling back three times in succession to signal the call’s importance. For now, tracers are not leaving messages or callback numbers.

The contact tracers, speaking from their prepared script, will inform the contact of approximately when they were exposed, and then take an inventory of symptoms, talk the contact through quarantine requirements, and help arrange assistance with food or housing if the contact cannot easily quarantine.

The new contact tracers began placing their first calls over the weekend.

“It was a real microscopic look into the lives of people who have this disease,” said Mr. Schwartz, the former civil rights lawyer, who reached around 10 people in his first eight-hour shift. To his relief, they all seemed eager to speak to him.

“Some people were lonely,” he said. “Some people were glad the state was involved. A few people named the governor by name.”

David Novak, 53, a social worker, found that his conversations were stretching to 30 or 40 minutes apiece, as the people he contacted told him about their difficulties maintaining distance from their family members.

One woman told him how strange it is, after a long marriage, to sleep away from her husband.

“This is where the human element of public health comes in,” Mr. Novak said. “You can use technology to make the humans more efficient, but if you take the humans out of it, how do you ask questions?”

“You’re going to have to talk to them,” he said.